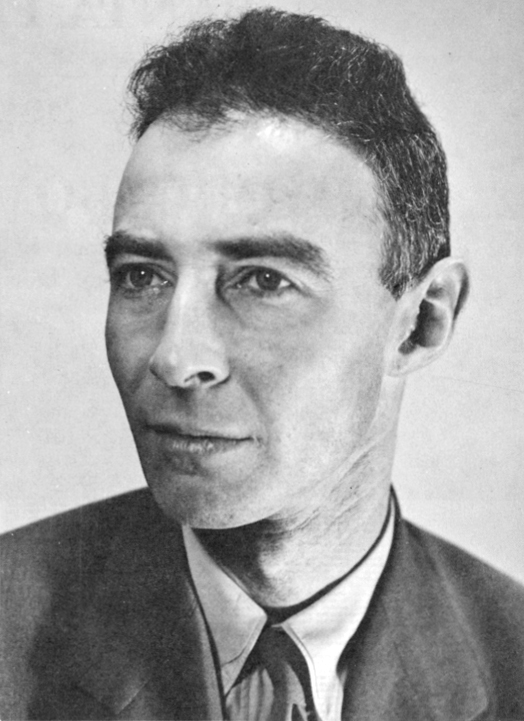

Note: UC's connection with Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) goes back to the Manhattan Project and Berkeley Professor J. Robert Oppenheimer's appointment as research director of the Project. UC has continued under various arrangements to play a managerial role at LANL as well as Lawrence Livermore and Lawrence Berkeley.

There is much Hollywood buzz at present about a new Oppenheimer movie (partly filmed at UCLA) due out in summer 2023.* When Jerry Brown was governor in his first iteration, he raised concerns about UC's link to nuclear weapons at the Regents. But since then, the issue has largely been dormant. The combination of the new movie and the developments described below could change that situation.

===

With Russia at war in Ukraine, US ramps up nuclear-weapons mission at Los Alamos. Is it a 'real necessity'?

A multi-billion-dollar project to make plutonium cores at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico may be unsafe and unnecessary. But proponents say national security is worth the risks.

Annabella Farmer | USA Today | 3-23-22

============

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- The radioactive cores of nuclear weapons – known as pits – haven’t been mass-produced in the U.S. since the end of the Cold War.

- The war in Ukraine has convinced some U.S. officials that the country must build up its nuclear weapons cache in the event of a showdown with Russia.

- Opponents say Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico “was never designed for this purpose" and "may never be safe" for such production.

============

LOS ALAMOS, N.M. — Los Alamos began as an “instant city,” springing from the Pajarito Plateau in 1943 at the dawn of the Atomic Age. More than 8,000 people flocked here to work for Los Alamos National Laboratory and related industries during the last years of World War II. Now the city may be on the brink of another boom as the federal government moves forward with what could be the most expensive warhead modernization program in U.S. history. Under the proposed plan, LANL will become home to an industrial-scale plant for manufacturing the radioactive cores of nuclear weapons – hollow spheres of plutonium that act as triggers for nuclear explosions. The ripple effects are already being felt.

Roads are planned to be widened to accommodate 2,500 extra workers. New housing developments areOppenheimer

appearing, one of them about a mile from large white tents that house drums of radioactive waste. And these are just the signs visible to the public: Within the lab, workers are busy around the clock to get facilities ready to produce the first plutonium core next year.

The cores – known as pits – haven’t been mass-produced since the end of the Cold War. But in 2018, under pressure from the Trump administration, the federal government called for at least 80 new pits to be manufactured each year, conservatively expected to cost $9 billion. After much infighting over the massive contract, plans call for Los Alamos to manufacture 30 pits annually and for the Savannah River Site in South Carolina to make the remaining 50.

The idea of implementing an immense nuclear program at Los Alamos has sparked outrage among citizens, nuclear watchdogs, scientists and arms control experts, who say the pit-production mission is neither safe nor necessary. Producing them at Los Alamos would force the lab into a role it isn’t equipped for – its plutonium facilities are too small, too old and lack important safety features, critics say. The lab has a long history of nuclear accidents that have killed, injured and endangered dozens if not scores of people. As recently as January, the National Nuclear Security Administration, the federal agency in charge of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, launched an investigation into a Jan. 7 leak at the lab that released radioactive material and contaminated six workers.

“We have a goal that’s not based in any real necessity, and that goal is leading to a rushed and therefore more expensive plan that’s more likely to fail,” said Stephen Young, an arms control and international security expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists, a national nonprofit organization whose mission is to use science to solve the world's most serious issues.

Criticism of the project has been so widespread, some believed – until as recently as last month – that it might even be tabled. But now, the war in Ukraine has put the project in the spotlight, prompting politicians and military leaders to say the U.S. must build up its nuclear weapons cache in the event of a showdown with Russia. “I would have said, pre-Ukraine, there was a chance it would have been shut down,” Young said.

The federal government, for its part, has long called the mission key to national security. For decades, multiple federal agencies have been trying to reestablish a large-scale program of pit production. In the backdrop, New Mexico politicians have fought hard for the billions of dollars and thousands of well-paying jobs the project is promised to bring. And the lab insists that manufacturing the pits will be safe and successful: “It’s a challenging milestone,” LANL spokesperson Jennifer Talhelm told Searchlight New Mexico. “But we are on track.”

Los Alamos National Laboratory produced the first plutonium pits as part of the Manhattan Project in 1945. One of these pits triggered the atomic bomb detonated at the Trinity Site in southern New Mexico, and one triggered the bomb called Fat Man that destroyed Nagasaki.

Since the end of World War II, pit production at Los Alamos has been largely limited to research and design purposes: The greatest number the lab has ever produced in a single year is 11. Now the goal is to nearly triple that number. The project’s opponents say that industrial-scale pit production at Los Alamos would mean a drastic shift in the lab’s purpose, requiring it to become something it was never intended to be. “There’s a whole host of engineering reasons why making pits at Los Alamos is a bad idea,” said Greg Mello, one of the project’s most vociferous and influential critics.

Together with his wife, Trish Williams-Mello, he has been meticulously monitoring the lab for more than 30 years and has been opposing the pit project since its inception. Los Alamos, he contended, “was never designed for this purpose. It’s not yet been made safe and may never be safe.”

Within LANL’s cramped, outdated facilities, pit production will require a huge influx of staff – some 2,500 technicians, security forces, facility operators, craft workers, engineers, scientists, professional staff and others – to perform what Mello describes as “a ballet of complexity,” working day and night to meet production goals. Indeed, last month, inspectors for the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board reported that renovations and other preparations for plutonium operations were underway seven days a week, 24 hours a day – an intensity that will “significantly ramp-up” in the long term, the board said.

Shift work is typical in the nuclear industry. But night shifts and the fatigue they cause can lead to “severe consequences to security, safety, production, and cost,” the Oak Ridge National Laboratory reported in 2020. The report pointed to shift work as a contributing factor in the 1979 reactor meltdown at Three Mile Island, the worst nuclear power plant accident in U.S. history. Federal reports, independent assessments, studies by the National Nuclear Security Administration and LANL itself offer a snapshot of the lab’s other shortcomings.

Among them:

In 2020, a withering report by the Government Accountability Office leveled a litany of criticisms at the plans to manufacture plutonium pits, noting that the NNSA – the agency that oversees LANL – has already spent billions of dollars and more than 20 years trying and failing to reestablish pit production. During that time, LANL twice had to suspend operations after the discovery of pervasive safety issues, including a nearly four-year shutdown that ended in 2016.

Even LANL has doubted its ability to succeed. The lab is only “marginally capable” of ramping up production to 30 pits per year by 2026 and sustaining that rate, it reported in 2018.

A 2017 assessment by the NNSA determined that relying solely on Los Alamos for pit production presented an “unacceptably high mission risk.” As a result of the NNSA assessment, the lab was taken out of the running for the pit project. It took intensive lobbying from New Mexico’s Congressional delegation over the next months before the federal government chose Los Alamos to share the mission.

Between 2005 and 2016, the lab’s “persistent and serious shortcomings in criticality safety” – involving potentially lethal nuclear reactions – was criticized in more than 40 reports by government agencies, safety experts and lab staff, an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity found. Officials at LANL declined to respond to Searchlight New Mexico’s multiple requests for comment. Talhelm, the lab's spokesperson, instead provided a written statement.

“The Laboratory is working to modernize facilities and hire new employees to begin pit production in support of our national security mission to ensure the safety and reliability of the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile. …We have the only facility in the country where this work is currently possible,” she wrote. “In 2018, NNSA completed an engineering assessment and workforce analysis of the site and found that it can safely meet the requirements of NNSA’s goal of producing at least 30 pits per year.”

Mello doesn’t agree with the lab’s assertions. In his view, the pit-production mission is folly. “The project is entirely unnecessary,” he said. And it will harm nearby Pueblos and communities, he added, “especially those who are nearest and most fragile.”

Called a hero by some, and difficult by others, Mello has devoted years to fighting and blocking nuclear-warhead projects at LANL, in tandem with his wife. Everyone who speaks of him does so with either enthusiastic or grudging respect for his work. The couple’s Albuquerque office is crammed with sensitive and classified documents that they’ve obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests and leaks from within federal agencies. In one case, Mello recalled, they used a stick to open an envelope in the yard, not knowing what was inside – it turned out to be a paper from a Pentagon source.

Mello’s background is in engineering, and he studied regional economics and environmental planning at Harvard. In 1989, he founded the nonpartisan Los Alamos Study Group, which has given briefings to the Department of Energy, the NNSA and others on Capitol Hill. Pit production at LANL is an accident waiting to happen, he believes. “We have no idea, really, what will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” he said. “But there are many possibilities.” History illustrates a number of them.

In 2011, for example, carelessness nearly led to catastrophe when technicians placed eight rods of plutonium side by side to snap a photo of them. This violated a fundamental rule of handling plutonium: Too much in one place can begin to react uncontrollably, generating a burst of lethal radiation. After this near-miss, LANL engineers in charge of worker safety resigned en masse, alleging that the lab prioritized profits over safety. The result was the nearly four-year shutdown.

There is yet another reason that opposition to the pit project is so fierce: Many experts believe it isn’t necessary. The project was launched in part because of debates about how age affects plutonium cores in existing nuclear warheads. Nuclear scientists and national laboratories say the pits in the U.S. arsenal will be stable and effective for more than a century.

Project proponents, however, say the pits are degrading and need replacement. As Admiral Charles Richard, commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, told the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services on March 8, there is an urgent need to “modernize the nuclear triad” in light of the war in Ukraine. Policy experts, for their part, worry that ramping up pit production will ratchet up international tensions.

“There is absolutely no reason to expand pit production capacity in light of Russia’s war in Ukraine,” said Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association. “That would suggest the United States should have a larger nuclear arsenal than we currently have, and that is a dangerous knee-jerk response.”

Even some of the most ardent supporters of pit production wish the country had better options, and express doubts about splitting the mission between two facilities. Admiral Richard is among them: It will be impossible for LANL and the South Carolina site to make 80 pits each year on schedule, he told the Senate on March 8. The Laboratory is working to modernize facilities and hire new employees to begin pit production in support of our national security mission to ensure the safety and reliability of the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile.

New Mexico politicians have nevertheless fought hard to bring the entire 80-per-year pit-production mission to LANL alone. When the NNSA issued a negative assessment of the lab in 2017 – dashing Los Alamos' hopes for the whole package – U.S. Sens. Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich and then-Congressman Ben Ray Luján wrote a scathing letter to the Department of Energy, demanding reconsideration. New Mexico lawmakers continue to voice support. As Heinrich told Searchlight last month, the state’s national labs “strengthen New Mexico’s economy by providing high-paying, high-skilled technology jobs.”

The money at stake is staggering: At least $9 billion for a decade of work at the two sites. Up to $3.9 billion of that will go to the Los Alamos lab, the NNSA says. But the real price tag could run as high as $18 billion over a decade, Arms Control Today reported.

To Mello, these aren’t only New Mexico’s problems – they’re the nation’s. “This is the decade when we have to change direction in this country,” he said. But changing direction isn’t easy. Any week now, the Biden administration is slated to release a document called a “Nuclear Posture Review,” which will determine whether the nation leans into nuclear amplification or reins it in. And if pit production proceeds at Los Alamos? It will cement New Mexico’s status as a “nuclear colony and sacrifice zone,” activists say.

In recent months, they’ve regularly left fresh flowers at a new plaque at the Santuario de Guadalupe in Santa Fe, commemorating Pope Francis’ condemnation of nuclear weapons. Activists from groups like Nuclear Watch New Mexico have continually lodged protests. Veterans for Peace, Tewa Women United, Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety and other organizations have gathered at the state Capitol to condemn the expansion of nuclear-waste storage in New Mexico – which pit manufacturing will require.

As 2023 approaches and pit production starts in earnest, the chorus of resistance is likely to grow louder. Whether Washington hears it is anyone’s guess.

Source: https://amp.usatoday.com/amp/7132121001.

===

*https://gamerant.com/oppenheimer-set-photos-locations-christopher-nolan/.

===

No comments:

Post a Comment